Rootless: An essay by Andy Bragen

Meet the Participants

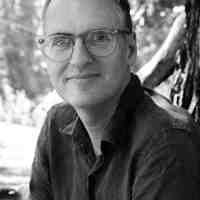

Andy Bragen (Author) honors include NYSCA and NYFA grants, Workspace and Process Space Residencies with the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, the Clubbed Thumb Biennial Commission, and a Jerome Fellowship. His produced plays include "This is My Office" (Playco), "Don’t You F**king Say a Word" (59e59/ABTP), and "Notes on My Mother’s Decline" (Playco/ABTP). Andy is an alum of New Dramatists, and has an MFA from Brown University. He teaches playwriting at Barnard College and at NYU Tisch.

After both his parents died, Andy Bragen, the playwright of Notes on My Mother’s Decline, had a choice to make: to leave New York, or not to leave? Earlier this year, Andy published an essay entitled Rootless, about this very question, and so much more. When his parents died, he was suddenly “rootless”, and to be rootless is to be free to go wherever calls to you. So, to leave New York, or not to leave? Notes on My Mother’s Decline is about his mother, which means it is also about where her life, their life, was. For his mother, New York was the only place for her. And so New York is where Andy grew up, and it is where his mother died. And somehow, it is also the only place for him. Rootless explores the process of his realization. Who would he and his family be, if not New Yorkers?

–

Sattley, California. Winter solstice 2016. We’re at my Aunt-in-law’s house, in the High Sierras, in the Egyptian room. Sphinxes, golden fabrics, a Nefertiti head. The rest of the house is faux Victorian, a modest ranch overstuffed with Costco products and kitsch. My wife, my toddler daughter, and I are curled up under an electric blanket in a bed so cushy and soft that it’s all we can do not to end up entirely entwined.

Sattley – Elevation 5000 feet, population 60. The snow is deep, and the winds are strong. There is nothing in this town, and while I have remembered to pack my stovetop espresso maker and organic Sumatran beans, I have forgotten the grinder. I will spend the day in a search for caffeine alternatives, making my way through last year’s chocolates, three Coca-Colas, and a Guinness Stout.

In the evening, the drumming will begin.

1963. Oakland. 525 Montclair Avenue. That’s the address on the bottom of a mimeographed poem written by my father. I found a whole series when I cleaned out his Secaucus, New Jersey condo in 2007. I punch in the address on Google street view. The neighborhood looks hilly and verdant. I bet I would’ve liked it there.

1963, East Village, NYC. My mother shares a tenement apartment on lower Second Avenue with her first husband Bill. She has to step over drunks to enter the building, and their apartment is broken into with regularity. And yet, she is delighted to be there. From early childhood, she’d dreamed of New York City, its freedom and its glamour, and its distance–geographic, political and emotional–from Jim Crow Mississippi.

Summer 2017. Graeagle. Plumas County. My wife and I have decided to micro-dose. They say it resets you, that it clears out the depression. New York brings the depression. I live in it, I feel it. When I get to California, I want it gone.

We each pop in a cap and start hiking upward.

On a rock overlooking a shimmering mountain lake, we bicker about east coast matters–careers, and money, and my jealousy, though I don’t acknowledge it, of my wife’s success and relative youth.

We sit there, in silence, steaming. I hate this place, and yet I never want to leave.

Oh California. I can’t quite handle you. I can’t quite make myself part of you. Should I ingest more psilocybin? Would that help?

Berkeley, 1965. My father goes out to protest on the steps of Sproul Hall and gets washed off of them by the police hoses. Did he break his leg? I remember that vaguely. I’d like to verify this, but there’s no one left to ask.

Once, around 1998, he was over at my place on 7th Street and Avenue C, and we were talking California. He says to me: the happiest days of my life, they were in Arcata, when I was teaching at Humboldt State. This would have been in the mid to late sixties I’d guess.

San Francisco 1987 – I’m getting stoned in Candlestick Park with the Polishook kid from North Jersey. His dad ran the CUNY teacher’s union, and my mom was a grievance officer. I’d come along with her for the annual convention.

San Fran was okay, but my mother never thought much of California, or the west in general, a region epitomized for her by Phoenix, where her little brother lived with his chirpy, earnest wife. Westerners had no sense of irony or sarcasm. Westerners were vapid.

My father, a native of Boston, had moved west in 1958, right after graduating college. He wanted to get as far away as possible from his overbearing parents. His brother had moved to California and then to Europe. My dad would have gone to Europe too, or even the moon, but he got into Berkeley.

He got a Master’s Degree in American Lit and drifted along, and somewhere along the way he headed up to Humboldt. For the happiest days of his life.

At the time, my mother’s marriage to Bill falling apart:“’I’ve met someone”, he told her. “A woman. A woman with no underwear.” My mother was “stunned.”

Did she actually tell me this? Or did I make it up? A little of both, probably.

1969 – New York City. A weekend party uptown, on York Avenue. My father is in from Terre Haute where he’s been teaching. He’s visiting his high school friend, the boyfriend, it turns out, of my mother’s roommate. My father and mother meet and spend the night together (talking, apparently). They discover they want the same thing, a child, and decide then and there to make a life together.

In June 1970, they will get married and in August 1971, I am born. Thanks to a friend’s overheard conversation at a party, they manage to acquire a rent control apartment in the East Village, on Fourth Street and Avenue A. Just $275 a month, a good deal even back then, for the three-bedrooms that they’ll fill with cigarette smoke and books. Unemployed during the first two years of my life, my father takes on the bulk of my care. And soon, he will quit academia and switch professions, beginning a career in market research. A good choice for him, it turned out, but seemingly contingent. His life could have been completely different. Hers—no. New York was the only path for her.

Nevada County, California, 2017 – we’re out here for over five weeks – a great escape from the career nonsense, from the steam rising in my brain. I’m also here to escape my bedridden mother. As her body has been failing, her needs and demands have been growing, partly due to our proximity – we live just across the street from her.

It’s a real vacation. I have my writing office, I jog, swim, play tennis. I take walks with my wife and daughter among the foothills, past blackberry brambles, and manzanita. New York can be hard on a marriage. My parents’ lasted just 15 years, 10 of which, maybe, were good. I’ve been with Crystal for 13 years, married for nearly six. It’s my greatest fear, that somehow I’ll fuck that up, that some part of me will lead me down my parents’ path, one of cruel words and mutual disregard, that I will end up, like each of them, old and alone.

I will come home from California that August and my mother will not be the same. She will seem foggy and unfocused, even weaker than usual, with a vacant look in her eyes. Even my three year old daughter will notice the difference. Early dementia? A UTI clouding her brain? Unclear, but whatever it was, it was the beginning of the end. She couldn’t read anymore – that’s what really clued me in. She could no longer retain plot.

If he’d stayed in California, what would my father have become? Would he have been healthier? And not so fat? Would he have avoided liver cancer? Would he have gotten his dissertation done and ended up at Humboldt State, or Chico State, or, somehow, Berkeley? Is there some parallel universe out there where I am fit, youthful, unneurotic and ruggedly handsome, a true blue Californian?

2017 – Solstice time. While my family is in Sattley, I’m alone on Avenue A, cleaning out my mother’s overstuffed rent control apartment. She’d had a stroke in early December, and died two weeks later. I clean with purpose and fury, with near madness, tossing out junk that dates back decades. All I want is to get the job done, and turn in the keys, as if by finishing this task I could somehow put my feelings behind me.

In Sattley, they’re drumming. In New York, back home in my apartment after a full day of cleanout work, I engage in my own ritual – making coin rolls out of my mother’s loose change. Pennies, nickels, quarters, dimes. I do it for hours, until it’s done, and then I count. One hundred fourteen dollars total.

I turned in the keys early, got the job done in just over a week. I threw away stuff that never should have been thrown out. Like her books: marinated in decades of cigarette smoke, they stunk. I didn’t have the patience to air them out, and so I boxed them up and threw them away. Looking back on that decision, I feel ashamed.

My parents are both gone. I’m rootless now. I’m free. Where do I want to live? Where do I want to die? Where would I feel least alone?

California, you tempt me. But New York, you’ve still got me, and you’re holding on tight. My life is here. My wife’s work and my own. My daughter’s school. Her friends, and ours. Our home. Who would I be, who would we be, if we weren’t New Yorkers?

2012 – Sierra City, California – our wedding, on a lawn in front of a rickety old house we’ve rented for the week, on the banks of the Yuba River. Crystal’s extended family is present, along with many of her California friends, and a couple of our closest New York friends. We’ve brought water scooped from the East River in Brooklyn Heights. We put it into a brass bowl, mixing it with water we’d scooped from the Yuba just that morning and offer remembrances of my dad, and my wife’s grandma, a native of those mountains, who’d just passed on. Then we pour the water, using a plastic New York Yankees mug from the 1980’s, onto the ground, by the base of the trunk. The water soaked down slowly, the earth already half-saturated from the morning rain. Technically, it’s illegal to mix coastal waters in this manner – there are concerns about parasites. But the tree still stands, as far as I know.

Related Productions

Introduction by

Anisa Threlkeld