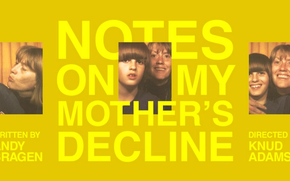

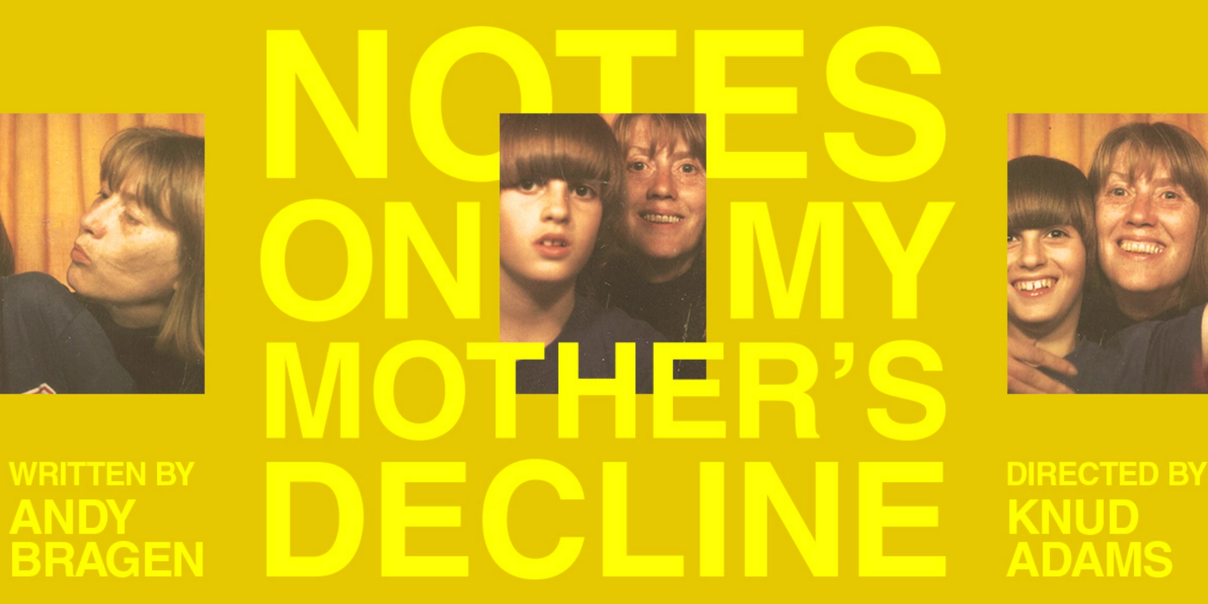

Mourning Memory: Make-believe

Playwright Andy Bragen discusses Notes On My Mother’s Decline as “the work of memory,” and as “engaged in acts of mourning.” (See the full exchange with John Brunner on the PlayCo HUB here.) Thinking about “the interplay between memory, and invention,” Bragen notes: “My mother’s voice, and her language, her self as I remember her are central to Notes On My Mother’s Decline.”

An inevitability of life, each of us is likely to experience loss, by death or some other means, of the presence of and connectedness to a loved one, someone from our inherited or chosen family. How do you honor the people you love after they die? What does it really mean to mourn a loss, the absence of a presence, person, or state of life that has already expired–or at least transformed enough to trigger the beginnings of grief? What is the work of memory, particularly when done in language? Does any memory last long enough to put suffering to rest? After the death or departure of someone you love, what remains but remains? There are as many answers as there are people. You can experience Andy’s answers to these questions starting October 6, 2019! To get ready for opening night, we’ll take a look at what a few other artists have postulated and put them in conversation with Notes On My Mother’s Decline.

Colm Toibin, in “What Is Real Is Imagined” (which Andy cites as an influence) poses an unapologetic break between what might ultimately be desired of acts of memory and the hard truth that is reality. If, caught in the rapture of memory, we feel we are making something more real or more sublime, we may simply be deluded. “What’s real is there now; the rest is memory, history and it hardly matters. This is a poor fact and will remain one whatever I do and whatever I write,” Toibin proclaims. What’s left to be done? Memory may not be as concrete as what is there now, whatever that might be; but are we ready to accept the notion that it matters little?

Even Toibin explains that memory readily provides a basis for narrative and form–constructed through the intuitive process of using “the power of cadence and rhythm in language” to give voice to memory. Indeed, Toibin suggests giving primacy to “the shape of the story [which arises out of memory] rather than the shape of life.” Building a composition, drawing from the writer’s experience and toiling with language until something more specific and more compelling than reality arises, is, for Toibin, memory at work in fiction. But what of life outside the creative realm (if the two can ever be separated)? What about when we need language to do more than “make things work for someone [we] will never meet?” What if there is more at stake than Toibin’s “sole responsibility […] to the reader?”

Toni Morrison has made an oeuvre, in part, out of memory. Her work forces us to critically examine memory and, thus, reaches beyond the singular reader to culture. In her essay, “Rememory,” Morrison acknowledges that history is, by definition, steeped in personal and collective perspective (both the former and the latter are shaped by the forces of hegemony). A central thrust of Morrison’s, she notes, has been to circumvent history, giving preference to the creative milieu that memory makes possible: “First was my effort to substitute and rely on memory rather than history because I knew I could not, should not, trust recorded history to give me the insight into the cultural specificity I wanted.”

This, of course, is echoed in Toibin’s assertion that history hardly matters. Both Toibin and Morrison find a richness in what is derived from language triggered by memory, which, as Toibin writes, “give[s] that writing a rhythm and a sound that will come from the nervous system rather than the mind…” Morrison’s process involves “trusting memory and culling from it theme and structure,” acknowledging that memory “ignites some process of invention.” This trust and subsequent culling evoke the type of long-term work Roland Barthes did, which we consider later. Morrison writes, in “Memory, Creation, and Fiction” that “memory (the deliberate act of remembering) is a form of willed creation. It is not an effort to find out the way it really was–that is research. The point is to dwell on the way it appeared and why it appeared in that particular way[…] What is useful–definitive–is the galaxy of emotion that accompanied the woman as I pursued my memory of her; not the woman herself.”

Bragen’s play, also partly in pursuit of a woman, his Mother, allows–in the ending–for the characters to escape what really happened, and get to “a place that neither of them could get to on their own.” It is clear that Toibin, without using these words, is postulating a similar jumping-point from memory that leads to form, and then is eventually fleshed out by some exquisite language. Morrison, however, is careful not to leave us with utopic notions alone, saying: “it is important that what I write not be merely literary.” She recognized narrative as a valid “form of knowledge.” It is here we find a connection with Roland Barthes’s mourning project.

Roland Barthes, whose notes-to-self following the death of his mother–a pursuit closer to Bragen’s–form what has been published as Mourning Diary, can help shed some light on the use of the power, the cadence and rhythm in language to move beyond fictionalizing toward healing and an end to personal suffering. Unlike our courageous playwright, Andy Bragen, Barthes began this series of writings after his mother’s death and was fearful of “making literature out of it.” Though he did eventually treat his mother in a text, admitting that “literature originates within these truths”–a conception similar to Toibin’s–he proclaimed “in taking these notes, I’m trusting myself to the banality that is in me.” Barthes used the diary-keeping both to find his own voice (several important works were generated while Barthes was making these notes) and to preserve his mother’s voice: “voice […] which is said to be the very texture of memory.”

Though we don’t have a diary that allows us to see Andy’s process the way Mourning Diary lays Barthes’s bare, we can see how acts of memory (regular diary entries in Barthes’s case) facilitate mourning, healing, the surfacing of language or voice, or a proper memorial for a loved one. Barthes writes: “My mourning is that of a loving relation, not that of an organization of life. It occurs in the words (words of love) that come to mind…” Barthes may not have moved as quickly into an intentional form–and he certainly bemoaned the wrapping-up of the worldly affairs of the dearly departed, calling it a “frenzied construction of the future (shifting furniture, etc.)”–but writing the words that surface during what Toni Morrison calls “rememory”–posited as “recollecting,” (distinct from remembering, posited as “reassembling”) –allowed Barthes to assuage, if only temporarily, his suffering. “Each of us has his own rhythm of suffering,” wrote Barthes: “Written to be remembered? Not to remind myself, but to oppose the laceration of forgetting as it reveals its absolute nature. The–prompt–’no trace remaining,’ anywhere, in anyone” [emphasis in original].

Barthes clearly understood Toibin’s assertion, that what is there now is real, but Barthes chose to leave more room for the reality of the spectre of what had been, to leave more room for traces. He writes: “We feel the need to create a sort of harmony between what the dear departed has been and what is offered after that being’s death.” Death has just as much to offer us as life.

It seems Barthes needed to arrive at that harmony first, before moving, with inspiration, to his writerly inclinations (a project that more closely resembles Andy Bragen’s): using rememory and remembering to mourn what has passed and shape a perspective for the future; honoring a loved-one; and, learning about himself and his relationship to his mother. Barthes notes: “Each subject (this appears ever more clearly) acts (struggles) to be ‘recognized.’ […] Before resuming sagely and stoically the course (quite unforeseen moreover) of the work, it is necessary for me (I feel this strongly) to write this book around maman. In a sense, therefore, it is as if I had to make maman recognized” [emphasis in original]. Barthes calls this: “Necessity of the ‘Monument.’ Memento illam vixisse.” Remember that she lived. Notes On My Mother’s Decline never fails to confront the very real complexities of a Mother’s living, separate from and inclusive of her children.

Related Productions

Written by

JuLondre Brown