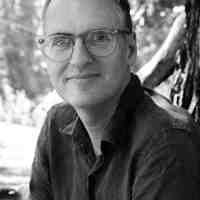

A Conversation With Playwright Andy Bragen

Meet the Participants

Andy Bragen (Author) honors include NYSCA and NYFA grants, Workspace and Process Space Residencies with the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, the Clubbed Thumb Biennial Commission, and a Jerome Fellowship. His produced plays include "This is My Office" (Playco), "Don’t You F**king Say a Word" (59e59/ABTP), and "Notes on My Mother’s Decline" (Playco/ABTP). Andy is an alum of New Dramatists, and has an MFA from Brown University. He teaches playwriting at Barnard College and at NYU Tisch.

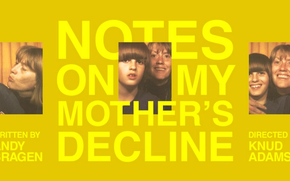

This fall, PlayCo will be co-producing Andy Bragen’s new play Notes On My Mother’s Decline alongside Andy Bragen Theatre Projects. PlayCo previously produced Bragen’s play This Is My Office which focused on the legacy of his late father and themes of identity and failure. As a companion piece, Notes On My Mother’s Decline is in a similar conversation with Bragen’s loss of his mother and also the birth of his first child. Andy Bragen, a native of New York’s Lower East Side, is a graduate of Brown University’s MFA program, an alumnus of New Dramatists, and a Lecturer at Barnard College. The show runs at the Next Door at New York Theatre Workshop October 6 – 27, 2019.

--

Andy, thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me. To start, what’s the origin of this play, Notes On My Mother’s Decline?

I started thinking about this piece, and writing some pages, right after This Is My Office closed in 2013. The This is My Office production was a wonderful and seminal experience for me as a writer. It is, like Notes on My Mother’s Decline, a very personal play, and to see it on stage, and share it with friends and colleagues here in my hometown meant a lot. At that time, my mother was starting to decline. She had a regular home health aide and there were things going on in her life, and in my communication with her, that had her on my mind in a pretty deep way. Also, at that time, my wife was pregnant with our daughter.

So, a lot of the themes of the play were on my mind when I wrote the first few pages of the play at the end of 2013. I started writing it as a dialogue but ended up cutting all the son’s responses to the mother. I wrote a very rough draft very quickly, finishing it within a few weeks of when my daughter was born. The play has changed very much since then but the impulse of that time, I think, remains central to it.

In this piece we see the Son becoming a parent while also losing a parent. That seems paramount to the play, both being someone’s son and being someone’s father. Do you agree?

Yes. Being a parent now has a lot to do with the play, especially in terms of my interest in and understanding of parent-child relationships. My parenting, my relationship to my own daughter, can’t help but be in relief to my relationship with my own parents.

Having a child has made me think a lot about my own childhood and that’s certainly something that this play reflects upon – a sense of New York City past and present. I’ve been writing essays as well, about my relationship to New York as a kid, and an adult, and my own kid’s relationship to New York. We live just across the street from where I grew up. So these same streets, these same playgrounds, all of this stuff is part of my daughter’s childhood. As much as the city’s changed, and it has changed immensely, there is a continuity of place and continuity, in some cases, of people. I feel deeply connected to the place where we live and to the stories that I tell my daughter about my childhood. So the work of memory has been interesting to me as a writer and as a parent.

How old is she now?

She’s five.

Do you think in writing this piece you discovered anything about either your childhood or your relationship to the neighborhood? Anything that you hadn’t previously really thought aboutThe work of memory seems to bring back more memories. I wrote so much of the play while my mother was still alive and I didn’t really crack open the ending until after she died. There are also certain things I’m understanding about my relationship to books and literature. Reading to my child connected me to my very vague memories of my mother reading to me. I found myself considering the different ways that we give independence to children. That’s not central to the play but it’s certainly essential to my thinking about it.

Also, during those last few years, life was hard for my mother and there are a lot of things that were not pleasant, for her, and for me, as both her son and as one of her caretakers. There are certain things that, as a writer, I had to let go of to focus on the craft, certain feelings of anger or frustration. There are a lot of things I continue to learn, about myself, and about my relationship with my mom, as I work on the play and think about the play.

Your mother was passionate about theater and went to shows frequently. What is it like memorializing her through an art form that she loved?

It’s something she really enjoyed. She came to New York from Mississippi in the 1950s on a high school trip to see Cat On A Hot Tin Roof. She always was someone very interested in stories. She had been in a very bad car accident when she was in high school and spent a year in traction, both in the hospital and at home. That must have been a very lonely time for her, and my sense is that, to get through it, she retreated into literature, and myth, dramas, and stories, into imagination. As an adult, here in New York, she went to plays all the time, mostly at uptown theatres, Broadway and Off-Broadway.

Theatre was an essential part of her. Even when she wasn’t leaving the house as much in her later years she did still go, in a wheelchair, to plays. It was one of the most important things to her, something she looked forward to. It made her very happy. She came to see a couple of my plays, including This Is My Office, which she said she was very moved by. I was glad to be able to share that play with her.

This is My Office and Notes on My Mother’s Decline have very different structures and narrative styles. What drove that divide?

I find that a play usually tells me what it is and most of my plays have different structures. My work has been pretty diverse in that regard. Almost every play has a different kind of form to it in the sense that the content tells me what the form is and vice versa- there’s a real interplay there. I write pretty instinctively, meaning that when I start, I don’t really know where a play is going.

With these two pieces, they’re both engaged in acts of mourning. They’re both engaged, to an extent, in forgiveness – be it about forgiving oneself or forgiving someone else. Office, with just one character, has to be about that character, ultimately. With Notes, however, there’s a place to go with both of these characters, some kind of discovery with them together, a place that neither of them could get to on their own. I think that’s sort of the formal discovery for me, a shift in the play that I couldn’t initially see. I didn’t discover the last ten pages of the play until last year, and I had been working on the play for a long time at that point.

You’re choosing to, obviously, speak very publicly about very difficult and private events in your life. Is there a fear or hesitation when you do that?

Well, I guess I’ll answer that question indirectly because, I don’t have the exact answer, but I might get to it as we’re talking. It is deeply personal. It is starting with truth and feelings and things that are important to me but the form and the play itself, the language, lead me forward as well. The personal approach is a way into telling a story that I think a lot of people can connect with, that I hope is more universal. For me, it’s the play I felt compelled to write. It exposes some sides of me that are not so nice. The character, Son, is both me and not. My plays start with something personal and evolve from there, all of them, even when my presence is hidden or disguised. With this play, I’ve tried to peel away a lot of the artifice, or at least to have the artifice be different, to get at some core questions about how we love, how we mourn, and how people die. As I said, I didn’t plan to tell the story in this way, but in the writing it felt right. It was the way I knew how to tell this story.

On that note, what’s your hope for the show’s audience? Do you have an aspiration for what they’ll be getting out of this play?

I hope they’ll be highly engaged with it and that they can connect it with their own relationship to family. I’ve had, in readings and workshops, conversations with different people and different generations who have had different reactions to the play. That has been very interesting to me.

Related Productions

Written by

John Brunner