A '9 Kinds of Silence' Reading List

Meet the Participants

Franziska Lee (she/they) is a rising senior studying English & Comparative Literature and Ethnicity & Race Studies at Columbia University. During the school year, she serves as a staff editor on 4 x 4 Literary Magazine and the Columbia Journal of Literary Criticism. She was previously the summer 2023 Artistic & Literary Intern at PlayCo.

Making its world premiere this September, Abhishek Majumdar’s 9 Kinds of Silence is a tense, haunting exploration of sound, silence, and the modern mythology of the nation-state. In a tent on the beach, patriotic mothers debrief the country’s sons as they return, victorious, from battle in the endless, finally ending war. But one soldier refuses to speak, and his silence threatens to undo him and his would-be confessor alike.

Assembled here is a scattering of readings that might keep the conversation going—or else feed the “fertile silence of awareness.” I’ve tried to move from more abstract theory on silence to books on nation and empire, and finally to poetry that reflects both the play’s thematic engagement with war and its formal preoccupation with language—poems that distrust the very medium that conveys them.

1. Speaking and Language: Defence of Poetry, Paul Goodman

Not speaking and speaking are both human ways of being in the world, and there are kinds and grades of each.

9 Kinds of Silence derives its title—and some of its lines—from Paul Goodman’s eccentric humanist criticism of linguistics, published in 1971. His defense of poetry is a defense of the only form of written language alive with the human spontaneity of speech; his concern with language is also, intimately, a concern with silence. Also of interest is Edward Said’s review in the New York Times.

2. “A Field of Silence,” Annie Dillard

I have seen, from behind the barn, the long roadside pastures heaped with silence. Behind the rooster, suddenly, I saw the silence heaped on the fields like trays.

A tiny, tremulous flash of a story published in The Atlantic, in 1978. Dillard captures a moment of transcendent stillness on the farmlands of the Pacific Northwest.

3. “How the Silence Makes the Music,” Corinna da Fonesca-Wollheim

“In my village, I learnt to sing. And my teacher, a pious man, said, ‘God lives between the notes.’” —so the mother tells the son in 9 Kinds. In this brief, lovely article for the New York Times, Fonseca-Wollheim walks us chronologically through the use of silence in the Western musical tradition.

4. The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, Carson McCullers

In his face there came to be a brooding peace that is seen most often in the faces of the very sorrowful or the very wise. But still he wandered through the streets of the town, always silent and alone.

Written when she was nineteen, McCullers’ desolate debut novel is set in a mill town in Georgia in the 1930s. Its protagonist, John Singer, is deaf and mute, and the novel follows his unlikely friendships with other people in the town as they search blunderingly for solace and understanding. “Hovering mockingly over her story of loneliness,” wrote Richard Wright, “are primitive religion, adolescent hope, the silence of deaf mutes—and all of these give the violent colors of the life she depicts a sheen of weird tenderness.”

5. Waiting for the Barbarians, J.M. Coetzee

What has made it impossible for us to live in time like fish in the water, like birds in air, like children? It is the fault of Empire! Empire has created the time of history.

Coetzee’s 1980 novel is narrated entirely by the aging magistrate of a settlement on the far frontier of an unnamed, waning empire. After the military launches a brutal new campaign against the indigenous population, the magistrate engages in a belated, futile act of rebellion. As his circumstances and dignity erode, he is forced to confront the violence obscured in his own gentlemanly bureaucratic form of colonialism.

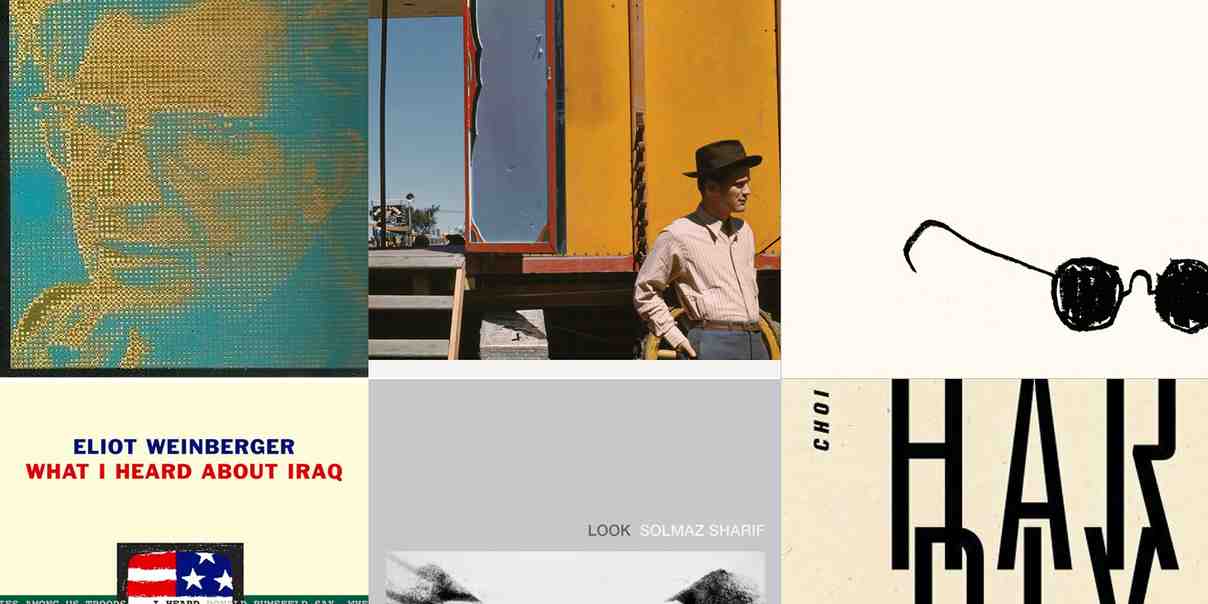

5. “What I Heard About Iraq,” Eliot Weinberger

I heard an Iraqi man say: ‘I swear I saw dogs eating the body of a woman.’I heard an Iraqi man say: ‘We have at least 700 dead. So many of them are children and women. The stench from the dead bodies in parts of the city is unbearable.’I heard Donald Rumsfeld say: ‘Death has a tendency to encourage a depressing view of war.’

Majumdar’s script is written to be adapted to the site of performance; like Waiting for the Barbarians, it takes place both here and nowhere—familiar but not identical. Emphasizing the familiar: in his 2005 essay for the London Review of Books, Weinberger delivers a montage of overheard facts, soundbites, and testimonials on the United States’ war in Iraq, revealing the hypocrisy and absurdism of the propaganda used to justify the war.

7. I am the Beggar of the World: Landays from Contemporary Afghanistan, translated and collected by Eliza Griswold

Be black with gunpowder or be bloodred / but don’t come home whole and disgrace my bed.

Griswold assembles over one hundred landays, rural Pashto folk couplets typically composed and recited by women. Witty and lilting, recounted in private circles or anonymously on the radio, the landays resonate with “a collective fury, a lament, an earthy joke, a love of home, a longing for the end of separation, a call to arms, all of which frustrate any facile image of a Pashtun woman as nothing but a mute ghost.” The collection of voices express complicated attitudes towards the U.S. occupation and the Taliban government, reflecting the complexity of subject position when the only recourse from imperialist aggression is a deeply reactionary and patriarchal nationalism, and personal agency comes with at the expense of sovereignty. I am the Beggar of the World draws attention to the sharpness of language from those whose silence is expected and enforced.

8. Look, Solmaz Sharif

Daily I sitwith the language they’ve madeof our languageto NEUTRALIZEthe CAPABILITY of LOW DOLLAR VALUE ITEMSlike you.

In her debut collection, Sharif lays bare the culpability of language in warfare—its cold neutrality, its euphemistic obfuscation of destruction. Strewing her verse with terms from the Department of Defense’s Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, she turns this mutilated and sterilized language back on itself, using it to criticize U.S. interventionism in the Middle East through intimate familial and personal narratives. At the same time, her poetry calls attention to the silence imposed by redaction, surveillance, and censorship, silence that falls in the archives of empire. In one haunting poem, for example, Sharif constructs a series of fictional letters to a Guantánamo detainee after they’ve been redacted—proper nouns erased, meaning clinging to the margins, love struggling to get through.

9. Hardly War, Don Mee Choi

To be born hardly, hardly after the hardliest of wars, is a matter of debate. Still going forward. We are, that is. Napalm again. This is THE BIG PICTURE. War and its masses. War and its men. War and its machines.

Dense and difficult, Choi’s avant garde collection is a work of “geopolitical poetics” attempting to “faintly imagine” the Korean War—which, despite four million casualties and more bombs dropped in three years than in the entire Pacific theater during World War 2, is remembered in the U.S. as the “Forgotten War”. Through hybrid forms—poetry, memoir, opera libretto, photos and artifacts—she investigates South Korea’s identity as a neo-colony of the U.S., including its role perpetrating imperialism in the Vietnam War, and her own position as a translator, including the political decision not to translate. Like in 9 Kinds, silence and illegibility are simultaneously conditions imposed by history and means of resisting or reclaiming it.

Related Productions

Curated by

Franziska Lee